.png)

Colorado State Fair art prize winner: Jason Allen (created by Midjourney)

Which is it:

Copyright infringement on an unprecedented scale and an existential threat to the artists, authors, musicians and software developers whose work it was trained on, which society should avoid rewarding with copyright protection?

Or just another useful creative tool for humans to use and no different to the fuss made about cameras in the late 1880s?

In 1884, a photograph of Oscar Wilde caused a stir in copyright law when a defendant (who had copied it without permission) argued that photographs should not attract copyright protection, because they have no human author. The photographer does not create the resulting image, it was argued: the camera does. All the photographer does is press the button. The Court disagreed, due to the level of creative intellectual control exercised by the photographer over the resulting image. Generative AI enthusiasts argue that generative AI is no different to works produced by a camera - the user inserting the prompt is like the photographer pressing the button - and its output should attract copyright in much the same way. It is just another useful creative tool for humans to use, they say.

But many artists, writers, code developers and musicians disagree.

Over the last year, a tidal wave of generative AI lawsuits have been launched against companies including Microsoft, GitHub, Meta, Stability AI, Open AI, Midjourney Inc and DeviantArt Inc, arguing that AI algorithms such as Stable Diffusion, Midjourney, Copilot, Codex, DreamUp, DreamStudio, LLaMA, GPT 3.5 and GPT 4 rely on copyright infringement on an unprecedented scale and threaten to decimate the creative professions of the authors whose works they were trained on. While massively popular, they are also massively illegal, it is claimed. Some are calling it “The Napster of the 2020s”.

These lawsuits allege that copyright infringement problems arise at two different stages: the initial training data input stage, and the final output stage.

The Training Input Issue

Generative AI algorithms that are trained on publicly available information (rather than proprietary datasets) are generally trained by scraping (i.e., copying) existing data inputs or content, such as books, artistic works, music and code. If the training data happens to be a copyright protected work owned by someone else, then (absent an available defence) this scraping would appear to amount to copyright infringement.

Generative AI trainers typically rely on the defence of “fair use” (fair dealing, in New Zealand) and specific text and data mining exceptions, which permit the copying of protected works for certain non-competitive purposes. In other words, the use must not compete with the purpose of the original author. These defences often require the use to be non-commercial, which makes them particularly appropriate for researchers at universities, and non-profits. The potential problem arises when these non-commercial entities license the resulting trained algorithm to commercial entities, which then charge customers fees for the creation of outputs. Those outputs arguably compete with the original content that the algorithm was trained on. The use of these defences by universities and non-profits to create algorithms which are then passed on to commercial entities (which ultimately compete with the original author of the training data) is a practice known as “data laundering”.

The US Supreme Court (USSC) recently weighed in on the limits of the fair use defence in the Warhol case (Andy Warhol Foundation v Goldsmith (May 2023) (SC)). Andy Warhol had copied photographs of musical artist Prince (which had originally been used to accompany an article about Prince) to make a series of silkscreen prints. Only one copy had been licensed by the photographer. Unbeknownst to her, Warhol had made several (unlicensed) copies, one of which was later used to accompany a magazine article about Prince upon his death. As the purpose of Warhol’s copy competed with the purpose of the original photograph, the USSC held this use was not transformative, and therefore not fair use. By contrast, Warhol’s (Campbells) canned soup series had been made, not for the purpose of selling soup, but for the arguably opposite purpose of critiquing consumerism. This purpose did not compete with the Campbells artwork and did qualify as fair use.

The Output Issue

The elements required to establish copyright infringement are:

- causal connection (including the ability to copy);

- the taking of a substantial part of the original; and

- objective similarity between the original work and the “new” work. Courts have said: “a copy is a copy if it looks like a copy”. Or in music cases: “a copy is a copy if it sounds like a copy” (Eight Mile Style LLC v New Zealand National Party [2017] NZHC 2603).

Many infringements do not even require any form of “wrongful” intention: it will infringe copyright in the original work to copy it, to issue copies of it to the public, or to perform it in public, even if you do not know that an infringement has occurred, although having such knowledge will increase the damages awarded. Copyright infringement has been established for subconscious and entirely unintentional copying of musical works (EMI Songs Australia Pty Limited v Larrikin Music Publishing Pty Limited [2011] FCAFC 47). Compounding this issue is the fact that, in some jurisdictions (such as the USA) it will infringe copyright to make a “derivative work”, being a new work that is identifiably “based on” or adapted from the original.

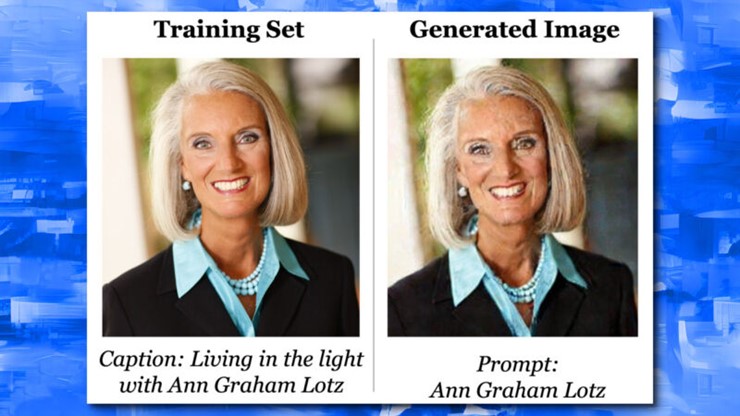

Recent generative AI lawsuits claim the outputs of AI algorithms trained on the plaintiffs’ works directly compete with their works and threaten to put them out of business. The plaintiffs allege these outputs are illegal copies of the plaintiffs’ works, or derivative works made from them. And there is some scientific support for these claims. AI researchers (Somepalli et al, 2022) suggest that while generative AI algorithms do not store copies of their training data, certain generative AI models can memorise that training data, which can result in the output looking very much like a copy of the training data, such as in the following example:

And this presents a risk for users of generative AI algorithms trained on copyright works without permission. Works that you use in your business may end up not only not protectable from use by third parties (most jurisdictions still require a human author for copyright subsistence - New Zealand and the UK are currently outliers on this front and New Zealand’s approach to AI copyright subsistence is currently under review) but also infringing the copyright of the authors of the training data.

Where to from here?

Until the outcome of the current suite of AI lawsuits is known, this issue will continue to present:

- a substantial risk to users of the generative AI featuring in these cases;

- a considerable risk to the developers of the generative AI models concerned; and

- a continuing concern to the authors who attempt to earn a living from the copyright granted to their works.

For these reasons, “legal” training datasets are now being created to train AI, comprising solely of public domain and licensed works, or training data that is proprietary to the generative AI tool developers, and some AI developers (such as Microsoft) are even providing indemnities to protect users from the risk of third party infringement claims.

If you have questions about your business’ development or use of generative AI or the steps you can take to protect your own copyright works, please get in touch with one of our experts.